When you think about therapy, you probably imagine someone sitting on a couch, talking about their day, their feelings, or their childhood. That’s what therapy for adults often looks like. But if a child or teenager needs help, it’s not the same. Not even close. Dětská psychoterapie doesn’t work with words alone. It works with play, drawings, silence, and sometimes even with the parents sitting in the next room.

Proč dětská psychoterapie není jen „malá verze“ dospělé terapie?

Adults come to therapy because they feel stuck, anxious, or overwhelmed. They can name their feelings. They can describe their thoughts. Kids? They don’t always have the words. A 7-year-old won’t say, “I’m experiencing separation anxiety.” They’ll scream when you leave them at school. They’ll cling to your leg. They’ll refuse to eat. Or they’ll shut down completely. That’s not defiance. That’s communication.

Therapy for children isn’t just about the child. It’s about the whole system around them - parents, siblings, teachers, even the school environment. If a child is struggling, it’s rarely just “the child’s problem.” More often, it’s a signal that something in their world needs adjusting. That’s why family therapy isn’t optional in child psychology - it’s the foundation.

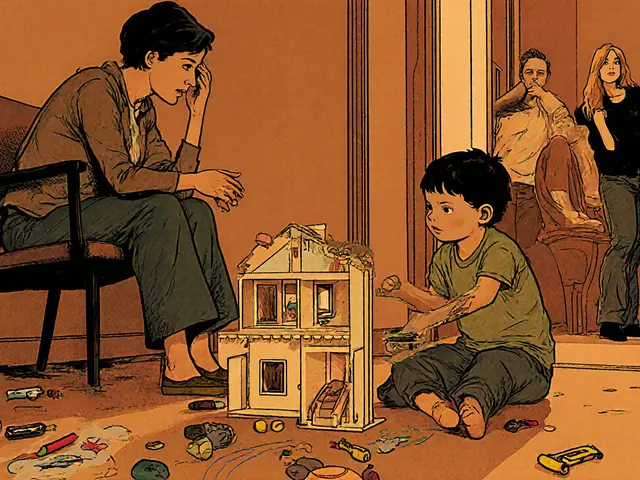

Unlike adult therapy, where the client is the sole focus, child therapy often starts with the adults. The parents are the ones who bring the child. They’re the ones who notice the changes. And they’re the ones who need to learn how to respond differently. A therapist might spend half the session talking to the mom and dad, while the child plays quietly with toys in the corner. That’s not ignoring the child. It’s helping the environment that holds them.

Co se děje ve skutečné terapii? Hra, kresba, pohyb

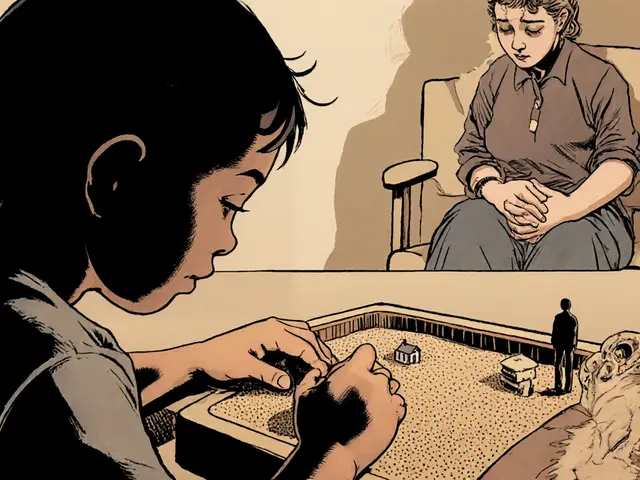

Imagine trying to talk to a 5-year-old about their fear of being alone. They don’t know what “fear” means. They don’t know how to sit still for 50 minutes. So therapists use play. A dollhouse. A sand tray. Puppets. Drawing. These aren’t just “fun activities.” They’re tools. Every drawing, every game, every movement carries meaning.

A child who draws the same dark house over and over? That’s not just art. It’s a window into their inner world. A boy who knocks over all the blocks during play? Maybe he’s acting out his anger at his parents’ divorce. A girl who refuses to speak for 10 sessions? Maybe she’s waiting to feel safe.

Therapists who work with young children are trained in developmental psychology. They know what’s normal at age 4, what’s unusual at age 8, and what might be a red flag at age 12. They don’t just listen - they observe. They notice how a child holds a crayon. How they react when a toy breaks. Whether they make eye contact. These small details tell more than words ever could.

For teenagers, things shift a bit. Around age 12, verbal therapy starts to become more useful. They can talk about friends, school stress, identity, or online bullying. But even then, it’s rarely just one-on-one. Parents are still involved - not to control, but to understand. A 15-year-old with depression might not tell their therapist they’re being bullied. But they might tell their mom. And the therapist needs to know that.

Co se diagnostikuje - a co ne

There’s a big difference between diagnosing a child and diagnosing an adult. You can’t diagnose a personality disorder in a 14-year-old. Not because they’re not struggling - but because their personality is still forming. The brain doesn’t finish developing until around age 25. So therapists look for patterns, not labels.

Common issues in children and teens include:

- Separation anxiety disorder - extreme fear when apart from parents

- Social anxiety - panic at school, parties, or group activities

- ADHD - not just “being hyper,” but trouble focusing, impulsivity, emotional regulation

- PTSD - after trauma, abuse, or even serious accidents

- Eating disorders - starting as young as 10 or 11

- Behavioral disorders - aggression, defiance, rule-breaking that goes beyond normal testing

And here’s something important: many childhood anxiety disorders don’t last into adulthood. Separation anxiety? Most kids outgrow it. But social anxiety? That one often turns into generalized anxiety or phobias later. That’s why early help matters - not to “fix” the child, but to give them tools before the patterns harden.

Proč je tak těžké dostat dítě k terapeutovi?

In the Czech Republic, there are only about 150 child psychiatrists for the whole country. That’s not enough. Most of them are overloaded. Many work in hospitals or clinics, but they can’t see every child who needs help.

So what happens? Kids wait. Six weeks. Sometimes longer. Meanwhile, school gets harder. Friends drift away. Parents feel helpless. And the child? They start believing they’re broken.

Psychologists can help, but they often can’t make diagnoses. Only psychiatrists can. And psychiatrists are in short supply. That creates a bottleneck. A child with severe anxiety might get a referral, but then sit on a waiting list for months. By then, the problem has grown.

And even when therapy starts, it’s not always easy. Some therapists focus only on the child and barely talk to the parents. That’s a mistake. Parents need to know what’s happening. They need to learn how to support their child at home. Therapy doesn’t work in a 45-minute session if the rest of the week is chaos.

Co dělá dobrého terapeuta pro děti?

A good child therapist doesn’t need a PhD to be trusted. They need patience. They need to be able to sit on the floor. To play with cars. To draw dragons. To not rush. To listen when a child says nothing at all.

They also need to be honest - with the child and with the parents. They don’t say, “It’s just a phase.” They say, “This is hard, and we can work on it together.” They don’t blame parents. They don’t label kids. They explain what’s happening in simple words: “Your brain is reacting to stress like a smoke alarm that’s too sensitive. We can teach it to calm down.”

The best child therapists connect with families. They send home simple exercises: “For the next week, when your child gets upset, sit with them for three minutes without fixing anything. Just say, ‘I’m here.’” They work with teachers. They help schools understand what a child needs.

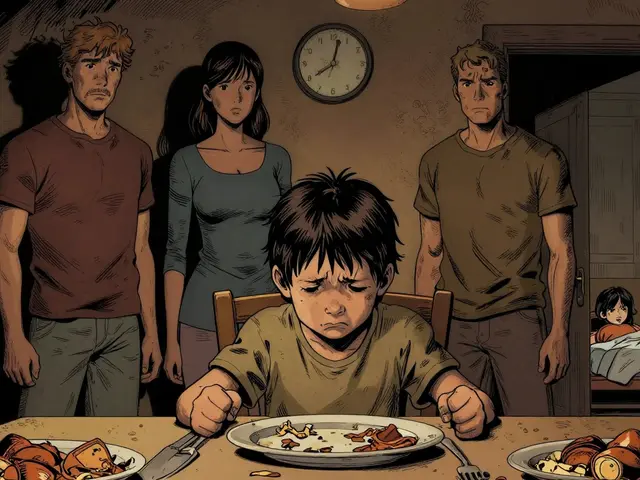

And they know this: healing doesn’t happen in the office. It happens at the dinner table. On the way to school. In the quiet moments before bed.

Co se mění - a co by se mělo změnit

There’s more awareness now than ever before. More parents are asking for help. More schools are trying to include psychologists. More people understand that mental health isn’t just for adults.

But the system is still broken. We need more trained child therapists. We need better coordination between schools, pediatricians, and mental health services. We need insurance to cover more sessions. We need to stop thinking of therapy as a last resort - and start seeing it as prevention.

Psychologist Peter Pöthe says it well: “The tendency to pathologize children’s normal emotions is enormous.” We’re not raising more broken kids. We’re raising kids in a world that’s faster, noisier, and lonelier. And we’re asking them to cope with it alone.

The solution isn’t more diagnoses. It’s more connection. More time. More listening. More adults who know how to be present - not perfect, just there.

If your child is struggling, you’re not failing. You’re paying attention. And that’s the first step.